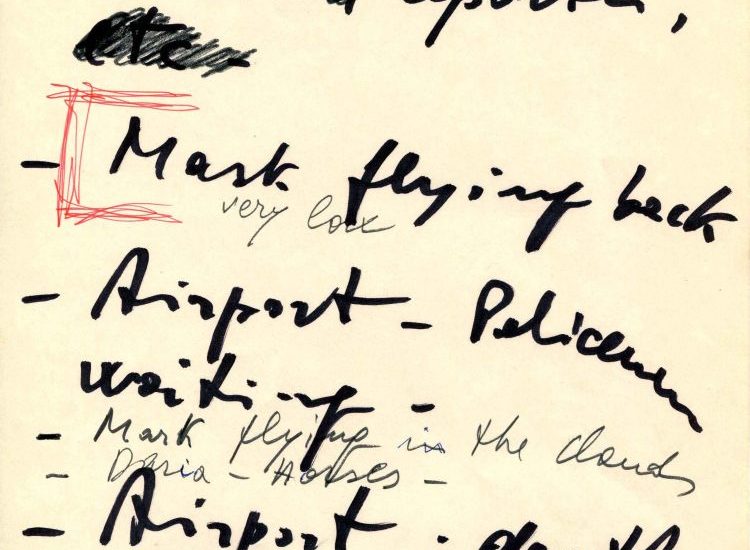

Of particular importance, for instance, are the various drafts of the treatment of Zabriskie Point (b. 8C/6, fasc. 52C), presenting characters, events and settings often very different from those of the film we know, as well as notebooks in which he kept annotations for dialogues or scenes of Il deserto rosso (b. 8C/4, fasc. 32A) agmentary documents, like collages composed of strips of handwritten or typewritten paper. These enigmatic materials are closely bound up with the years of his illness, but also make it possible to explore the working methods characteristic of the previous phases of his career. Unable to work normally due to the stroke he had had in 1985, Antonioni had begun to produce new material by cutting out and rearranging notes written in previous decades. In this way he turned the original documents into something new, a collection of aphorisms and reflections that he would later publish with Il Girasole: A volte si fissa un punto (1992) and Comincio a capire (1999). However, by examining Antonioni’s notes as a whole, one realises that this working method was already an integral part of his writing practice. Ideas barely sketched out and then discarded would thus become, several years later, new materials. This is the case of the first version of the fairy tale Giovanna tells her son in Deserto rosso (Red Desert). Removed from the screenplay and subsequently replaced by the sequence we know, this piece would reappear almost ten years later, becoming the subject of a new film L’aquilone (b. 8C/4, fasc. 40), which the director tried unsuccessfully to direct in Uzbekistan in the second half of the 1970s.

Back to focus